Capacity Factor, April 2024

Good morning, and happy spring. Enjoy this month's edition of Capacity Factor, with a couple of updates on clean energy deployment, some thoughts on industrial policy, and a closer look at a recent affordable housing claim.

Yakov Feygin — Geothermal Liftoff

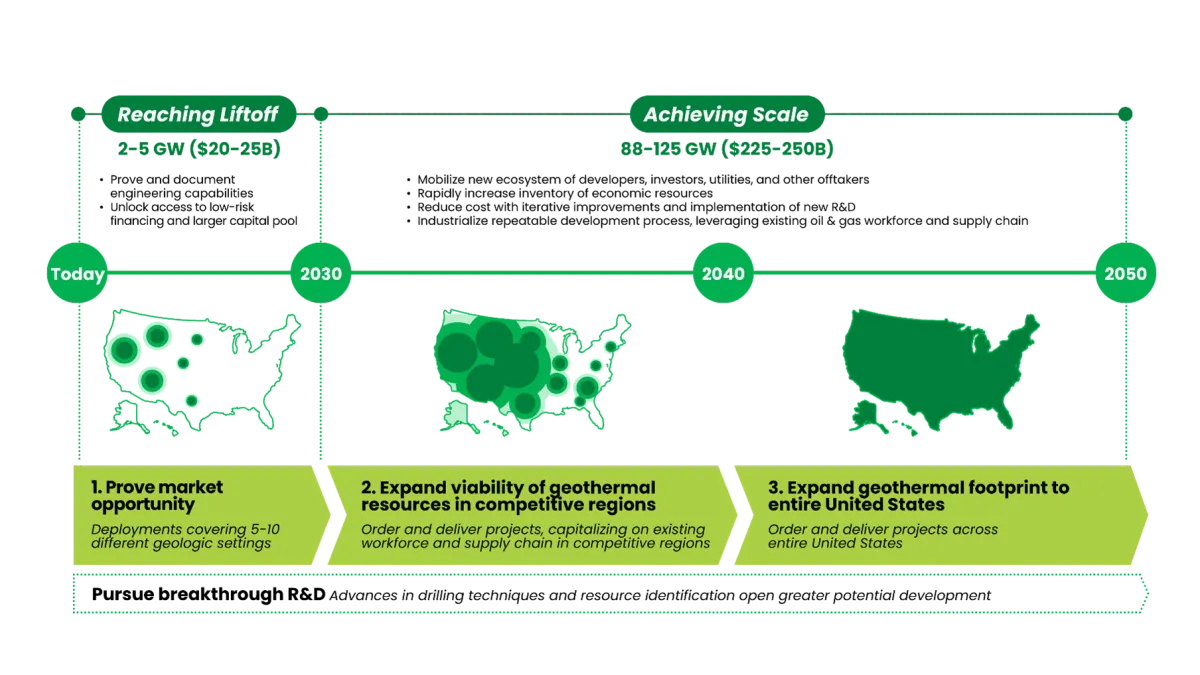

The Department of Energy (DOE) released another commercial liftoff report, this time focused on enhanced geothermal energy. While all of their reports are excellent, this one features a wonderful discussion of how the changing grid shapes the price of geothermal energy—with many broader implications for energy finance writ large.

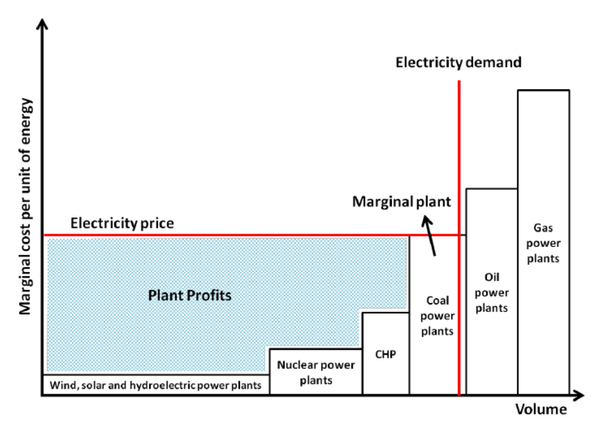

Increased variable renewable energy (VRE) penetration means that utilities are placing a premium on the ability of resources to “peak” in high demand periods. Specific industrial clients are looking for “clean firm” resources to avoid even minor fluctuations in electrical supply, which VRE cannot promise absent a massive expansion of long-term storage, which is in itself imperfect. Thus, the DOE's report points out that the price of advanced geothermal, which is one of the most dispatchable, firm carbon-free energy resources, is going to be higher even as VREs otherwise bring the marginal price of electricity down because customers will want its “firm” attributes. The economics of advanced geothermal are better in a VRE dominated grid than they would be otherwise.

The DOE's report draws on another exceptional study by the University of Texas. The study’s authors dove into the comparative economics of the oil and gas sector and the geothermal industry. Both industries face a lot of the same costs and require similar technologies, and workforce. Geothermal should be less risky because its products do not suffer from the same high price volatility as oil and gas. Most electricity is delivered on long term contracts, which means that consumers/offtakers completely absorb price risks. Therefore, before taking into account policy incentives, a private sector investment committee has a hurdle rate of around 15-20% return on equity for an oil and gas project, compared to a 12-15% return for a geothermal project with the same costs and risks.

So why isn’t every oil and gas investor piling into geothermal if it promises both higher returns and lower hurdle rates? The new generation of geothermal energy resources might not be as risky as oil and gas but it is more uncertain by virtue of its novelty. As Keynes pointed out in the General Theory, investors can assign probabilities, and prices, to risk, but not to uncertainty. Measures and perceptions of risk inform how investors distribute capital across their portfolios of investments, but uncertainty determines if investing in a certain asset is even an option. Enhanced geothermal has made leaps but still suffers from high uncertainty related to the deployment of a new technology at scale, environmental risks and regulations, and plant design replicability. This explains why investment into advanced geothermal comes from venture capital, which speculates on degrees of uncertainty, rather than the larger, cheaper pools of debt financing that energy projects usually benefit from.

The IRA has extended tax credits to the geothermal sector, and the LPO is planning to invest as well. This government action might be constituted as “de-risking” the sector for private capital. However, a better way to think about these programs is that they are aimed at familiarizing private investors with a new technology, like advanced geothermal, by rapidly scaling its deployment and identifying the importance of non-financial barriers that create uncertainties for firms. Increased familiarity provides the basis by which risks can be understood and further policies considered. So, in this instance, IRA isn’t just de-risking, but converting uncertainty into risk.

Chirag Lala — Discipline and Industrial Policy

I recently published a working paper on tax credits and derisking. The paper was inspired by a debate (see here, here, here) on whether it is advisable to give private firms something so they undertake investment. Critics of this “derisking” approach argue that successful industrial policies require the state to discipline the private sector through legal or financial penalties that force firms to pursue public objectives.

The trouble is, that this critique of a subsidies first policy misunderstands the investment process. Firms will acquire, manufacture, or install capital equipment if they feel confident that projects will make sufficiently sizable or stable profits. The riskier the project, or the more uncertainties it faces, the more “sufficiently sizable” the gains will have to be. Sometimes, investment barriers are so difficult that no prospective gain (or risk) can be calculated—so no investment is attempted. At some point investment barriers become less about the risk of future returns, but about an inability to conceive of any future. In its most extreme, this fundamental uncertainty means that new technologies will not be considered viable for scaling.

However, firms face potential risks from not investing too: lost market share, an unproductive asset mix, supply chain vulnerabilities, etc. They weigh these risks against the costs that various market-, technological-, financial-, and infrastructural-obstacles might impose on them. By dramatically lowering the cost of capital on projects, tax credits, for example, actually remove a critical investment barrier. Now more firms will invest in more energy than they otherwise would, putting pressure on those who do not. This is also a form of discipline: forcing laggards to invest or pass up opportunities their competitors will take.

The issue critics will point to is how to ensure firms actually invest rather than pocket subsidies. The answer is to impose conditionality: a societal ask in exchange for derisking. Take the investment tax credit: it requires energy projects to be completed before money is disbursed. To build on this approach, we need to determine where and how investment barriers prevent desirable results. We must also remember that certain conditionalities or policy targets only succeed if other investments have already happened: for example, helping firms meet domestic content requirements may require further investments in domestic production. Accordingly, policymakers need mechanisms to select, prioritize, sequence, and de-risk investments, as well as monitor their progress. This, not discipline, is the true work of industrial policy.

Advait Arun — Solar Insecuritization

In our first newsletter, Yakov commented on the ailing financial health of California’s rooftop solar industry, an effect of higher interest rates and lower “net metering” reimbursement rates for homeowners. Alana Semuels’ recent TIME feature on the 2008-esque “financialization” of rooftop solar uncovers one other source of its fragility. She highlights how solar companies’ business models rely on subscribing as many homeowners as possible to solar loans and leases, aggregating those portfolios into securities, and offloading those debts to Wall Street to raise more debt. Thanks to higher interest rates and defaulting loans, these companies cannot refinance their immense leverage. In their rush to generate more loan volume, they resorted to predatory loan tactics: customers allege that they didn’t realize they had signed up for loans, that they were promised bill savings that never materialized, they were promised tax refunds they weren’t actually eligible for, or they paid extremely marked-up prices without being able to evaluate the cost breakdown.

Semuel’s scoop should be a warning to policymakers and community leaders preparing to use the IRA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) to establish low-cost rooftop solar financing programs for low-income communities. GGRF lenders are required, by statute, to leverage private capital, primarily by offering incentives for private co-investment such as first-loss protection—but they’re operating in the financial environment Semuels is describing. As Wall Street loses interest in a rooftop solar asset class, in part thanks to higher interest rates, it might not be so easy for rooftop solar market participants, public or private, to find opportunities to securitize and offload their portfolios, forcing them to choose between financing more projects and staying liquid.

Market confidence generates loans and capital expenditure, but evaporates when the returns fall short of expectations. Policymakers must ensure that the most vulnerable aren’t saddled with the consequences. The GGRF’s success in the distributed energy sector requires these financial markets to have a public backstop, to prevent yesterday’s investment euphoria from constraining investment and harming low-income communities today. In the absence of a Freddie Mac for solar, the GGRF’s green banks are our best available secondary market backstops; with their lower financing costs, they should buy up portfolios of solar asset-backed securities at relative discounts to ensure that the asset class stays liquid.

Of course, the energy transition is nothing but uncertain returns; utility-scale solar will require similar interventions. But, seriously, why pursue this financial model for rooftop solar in the first place? I’m reminded of failed “financial inclusion” efforts in the United States and abroad: creating a system of subsidized loans for low-income consumers merely allows rent-seeking middlemen to take a cut of the returns, paid for by many loan recipients’ greater indebtedness. Why should anyone encourage individual homeowners and renters, low-income ones in particular, to take out more debt on an asset with uncertain returns on bill savings—rather than, say, building utility-scale solar and virtual power plants aggregating DERs to serve everyone at once while providing electricity rebates to low-income ratepayers? Decarbonization shouldn’t put individual people into more debt.

Paul Williams — Free Lunch for Affordable Housing?

Earlier this month, the Wall Street Journal ran a story with an explosive claim: "Private Developers Are Rejecting Government Money for Affordable Housing". In reality, the builders are replacing one source of government money with another source of government money. In doing so, they're taking on a little more risk, but with the opportunity for more reward. Remember, the law of one price is still in effect.

Last year, we ran a post on our blog on the logistics of public development that included a brief explanation of the two primary federal sources of housing subsidy, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and the Section 8 voucher. With the LIHTC...

for, say, a $50 million project, the [LIHTC] sale may generate $20 million in equity. That means that the mortgage on the project can be reduced to $30 million, which lowers the monthly payments that the affordable housing developer needs to make on their debt service. Think of it as akin to a down payment on a home: the larger the down payment, the lower your monthly payments will be. For an affordable housing developer this means that they can rent the units at affordable prices while still being able to cover their costs.

Whereas for the Section 8 voucher...

Rather than putting money up front at construction time, vouchers are a guarantee of rental income over the long term. Tenants pay 30% of their income toward rent, and HUD tops up those tenant payments close to the market rate level to cover the costs on larger mortgage payments.

What's happening with the developments described in the Journal article is, rather than applying for LIHTCs at construction time, the developers are relying on renting to families with Section 8 vouchers instead. They're certainly taking on a higher level of risk by doing so—there's no guarantee they'll be able to fill the units with voucher tenants. But to compensate for that risk, there's the potential reward of significantly higher rent payments every month, paid by HUD.

I think it was Milton Friedman who said "there's no such thing as free affordable housing", right?