Capacity Factor, June 2024

Since last month's newsletter, CPE has welcomed two new team members: Sheree Bouchee, Director of Housing, joins us from Arizona's Department of Housing and Ashwin Warrior, Deputy Director of Housing, joins us from HUD's Multifamily division. Thanks to this new capacity, we'll now be able to maintain a better balance covering innovations across the energy and housing sectors.

Yakov Feygin and Chirag Lala — FERC Order 1920

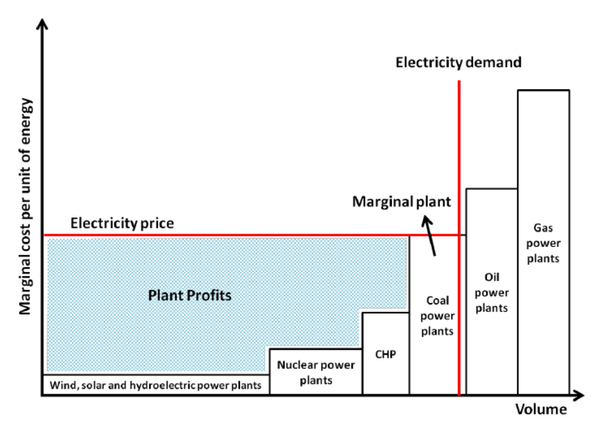

On May 12, 2024, FERC published Order No. 1920, which established new requirements for transmission operators—known as ISOs or RTOs—to plan regional transmission. This rule is the most transformative change to the way regional transmission is planned that the United States has seen in decades: it requires grid operators – mainly ISOs/RTOs – to proactively plan intra-regional transmission ahead of new load and more evenly allocate investment costs between beneficiaries.

The rule explicitly allows for and encourages planning processes to treat insufficient infrastructure or congestion as a basis for justifying new projects. Ideally, grid planners will take this opportunity to now identify the capacity needs of the grid well before new projects are ready to interconnect. This would cut down on long interconnection queues, one of the biggest barriers to the rapid deployment of clean energy.

The rule also established a procedure to better determine the distribution of transmission upgrade costs among numerous beneficiaries. Rather than allocating the cost of all grid upgrades to the first project in the queue that requires them, (See Chirag’s May newsletter section on the problems created by the “cost causation” principle and insufficient anticipatory planning in existing interconnection processes), it creates a set of rules for negotiations between developers and the state regulatory which govern cost allocation.

Applicants looking to build new interstate lines may engage in a six month process with relevant state entities to agree on a method of cost allocation to pay for intra-regional facilities that cross state boundaries. In the event that there are disputes over this proposal and an agreement between the relevant parties cannot be reached, priority projects identified by the planning process will automatically be assigned the default method of allocating costs based on proposals to FERC. This provision removes the ability of an individual state to block new projects by stonewalling on cost allocation. This provision has spurred resistance from red states who believe that it forces them to pay for new transmission to facilitate clean energy projects that are required by regulations in neighboring states.

Order 1920 is groundbreaking—but it is only the first step in a much longer process. As FERC commissioner Allison Clements pointed out, the order does not provide a mechanism to mandate the selection of a particular project by a utility. In other words, FERC has created a process but not a means of implementing it. While we wait for national solutions to develop a more efficient grid, states can and should take (and some have already taken) the lead to establish their own public transmission developers and speed up implementation absent further regulation or legislative reform. States should also begin designing similar rules for their distribution system interconnection rules.

Advait Arun — Domestic content safe harbor

The US Treasury comes bearing good tidings: finally, a “safe harbor” regulation for the domestic content requirements binding developers of clean energy projects. Federal domestic content requirements force clean energy developers with federal financing to affirm that a certain percentage of the manufactured products that they use, as measured by the costs of those products as percentage of total project costs, are manufactured in the United States. If they do, they get a bonus to their tax credit. But because manufacturers are reluctant to divulge their costs, it’s hard for developers to know if they’ve met domestic content requirements.

The new safe harbor rules are a relief for developers: rather than struggle to secure their manufacturers’ cost structures, they can use federally provided tables of assumed cost structures depending on their project type. The tables themselves list the main manufactured products in each project type and provide each product’s components’ assumed percentage share of the total project cost. The table for batteries looks like this:

(APC seems to stand for Applicable Project Component, MPC for Manufactured Product Component.)

All a developer needs to do is add up the assumed cost percentages of all the components they sourced from American manufacturers. If the total percentage is higher than the legal domestic content threshold, they can attest to having met the domestic content requirement. A battery developer that acquires battery cells and a thermal management system produced in the United States clears the statutory 40% domestic content threshold (38% + 4.9% = 42.9%), even if all other parts of the battery pack are imported. If the developer imported some share of the cells—say, 10%—then it should factor that into its total domestic content percentage ((38% x 0.9) + 4.9% = 39.1%). If the developer procures all components of a battery pack in the United States, it can add the assumed cost percentage of production itself (here, 21.1%) toward its domestic content total (38% + 3.3% + 4.9% + 5.2% + 21.1% = 72.5%).

Developers cannot pick and choose between the cost percentages in these tables and the actual cost percentages provided to them by manufacturers, if applicable. They must either affirm domestic content compliance using this safe harbor table or using information from manufacturers.

CPE encourages everyone to check out the safe harbor tables (they’re easily accessible here) to get a sense for which manufactured components for which the government clearly wants to speed up on-shoring. It’s worth remembering that all steel and iron structural materials in these projects must already be US-made for the projects to qualify—these are construction materials, rather than manufactured components—and that the 40% threshold rises to 45% for projects starting construction next year, with further rises ahead. (Some project types have other thresholds.)

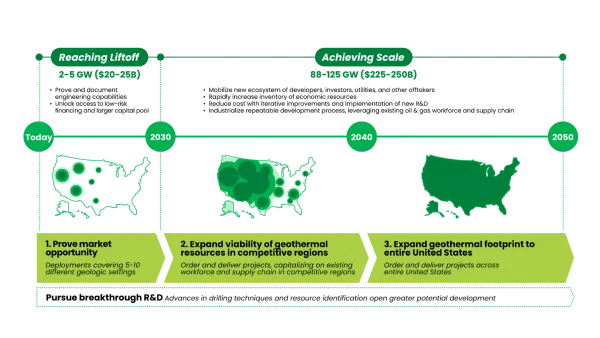

The rules currently provide these safe harbor tables for solar PV, onshore wind, and batteries, with offshore wind, geothermal. Other more ambitious project types will see forthcoming guidance. We still do not have guidance on how these tables might apply to brownfield projects where existing infrastructure is repurposed. The new guidance entirely ignores elective pay—which is worrying, because elective pay-eligible entities cannot access elective pay at all if their projects fail to meet domestic content. Treasury is asking for additional comments by July 15 to get a sense of what other project types it should add, and how often it should update these tables. Hopefully it fills in these blanks, too.

Ashwin Warrior - Montgomery County Wins Prestigious Ivory Prize for Housing Production Fund

Our friends over at the Housing Opportunities Commission (HOC) received the 2024 Ivory Prize for Finance for their Housing Production Fund model last month. The Ivory Prize is awarded annually to recognize ambitious and innovative solutions to the housing affordability crisis with a special focus on solutions that combine elements of finance, policy, and design and construction. HOC deserves it!

The Montgomery County model, as we’ve written about before, is a creative way for cities to supplement their production of mixed-income affordable housing by (1) deploying a municipal revolving loan fund to provide low-cost construction finance to potential projects, (2) providing a source of low-cost senior debt, accessed via a state’s Housing Finance Agency (HFA) and the Section 542(c) HFA Risk Share program, and (3) securing mission-aligned permanent financing to take out the revolving loan fund investment so it can be used for future projects. These three components, combined with property tax exemptions enabled via public ownership, have the potential to reduce project costs and enable sustainable mixed income development, with roughly 30% of units in a project serving residents making 50-80% of the Area Median Income, with the rest rented at market rate.

The model has caught the eye of the New York Times, HUD, the White House, and cities throughout the country looking to expand the production of mixed-income affordable housing. By our count, there is roughly $283 million of public investment in revolving loan funds for construction finance and over 5,000 units built or in project pipelines using this model or variations of it.

The video highlighting Montgomery County’s award—and the sleek interiors of their new project The Laureate—is well worth the watch. If cities can achieve this level of affordability without drawing upon LIHTC or other federal subsidies, scarce affordable housing resources can be deployed where they are needed most.

Center for Public Enterprise is assisting cities and states throughout the country to replicate the model in their own communities. If you’re interested, get in touch. Learn more about the other 2024 Ivory Prize winners here.

Sheree Bouchee - Arizona’s Housing Legislative Wins

We are happy to share four (4) innovative housing production solutions recently signed into law by Arizona Governor Hobbs. These laws will create a pathway for increased housing production, decreased regulatory restrictions and streamline approvals. A summary of each housing law is listed below:

House Bill 2297 (commercial buildings; adaptive reuse) allows for adaptive re-use of commercial to residential buildings (in municipalities with populations at or above 150,000) without requiring a conditional use permit or other rezoning process. Another game changing element of HB2297 is related to the height and density allowances. Which allows the project to align with the maximum height and density allowable within one mile of the project site. If the allowable height is less than the existing height of the commercial building, the existing height can remain, and the density can be expanded to maximum allowable density.

House Bill 2720 (accessory dwelling units; requirements.) allows any single-family dwelling (in a municipality with a population greater than 75,000 people) the right to add two (2) accessory dwelling units (one (1) attached and one (1) detached). If the lot is one acre or larger the property may increase to two (2) detached accessory dwelling units (if one unit includes a restricted affordable dwelling unit).

House Bill 2721 (municipal zoning; middle housing) requires municipalities (with a population greater than 75,000) to allow duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and townhomes as a permitted use on all lots zoned single family with one mile of a municipalities central business district and up to 20% of any new development with more than ten (10) contiguous acres.

Senate Bill 1162 (residential zoning; housing; assessment; hearings) Streamlines zoning approvals by requiring municipalities to finalize zoning decisions within 180 days. The legislation also requires municipalities with populations equal or greater than 30,000 to submit a five-year housing needs assessment and annual performance report.

Arizona identified key barriers within existing zoning codes that were limiting housing production and created targeted innovative solutions. These legislative changes mark a significant step forward in addressing housing affordability and availability challenges in Arizona.