Capacity Factor, March 2024

Yes, we know—it's not March yet. But February 29th is kind of a fake date—excess capacity, if you will.

Anyway, we're settling into a rhythm here with Capacity Factor, with each of our authors choosing one primary article to highlight and dive into with discussion and commentary. This month, we cover two grid-related topics (ELCC and ERCOT), housing construction that is stalled—not by zoning, but by financing, and transaction costs (broadly construed) for financing energy projects.

Chirag Lala — Effective load carrying capacity (ELCC)

Mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM recently published 2025-26 estimates of “effective load carrying capability” (ELCC) that show gas plants carrying more load (a measure of electricity demand), on average, than any of the four battery storage options during peak energy demand events. This statistic, which starkly contradicts PJM’s 2024-25 estimates, is huge: PJM might use it to argue for building more gas capacity. But why?

PJM's 2025/2026 ELCCs are pretty wild. Just 62% for gas combustion turbines -- roughly on par with 4-hr storage and significantly less than demand response (77%!).

— tyler fitch (@ty_fi) February 9, 2024

Looks like assumptions about steady-state gas supply and operations need updating. https://t.co/xHMKtZ2lmU pic.twitter.com/GGNHp9hYMH

Utility planners calculate the ELCC by simulating grid disturbances and seeing how often a resource can meet the resulting load. If batteries provide an average of 80 MW across multiple 100 MW load event simulations, their ELCC is 80%.

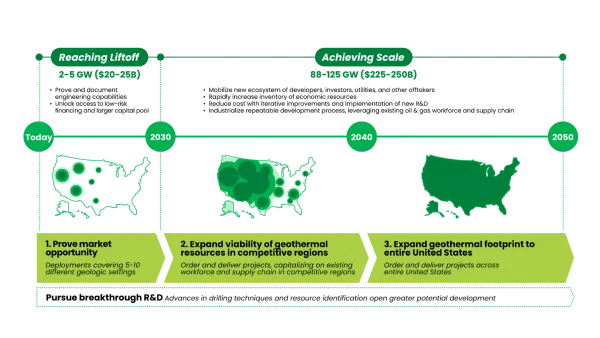

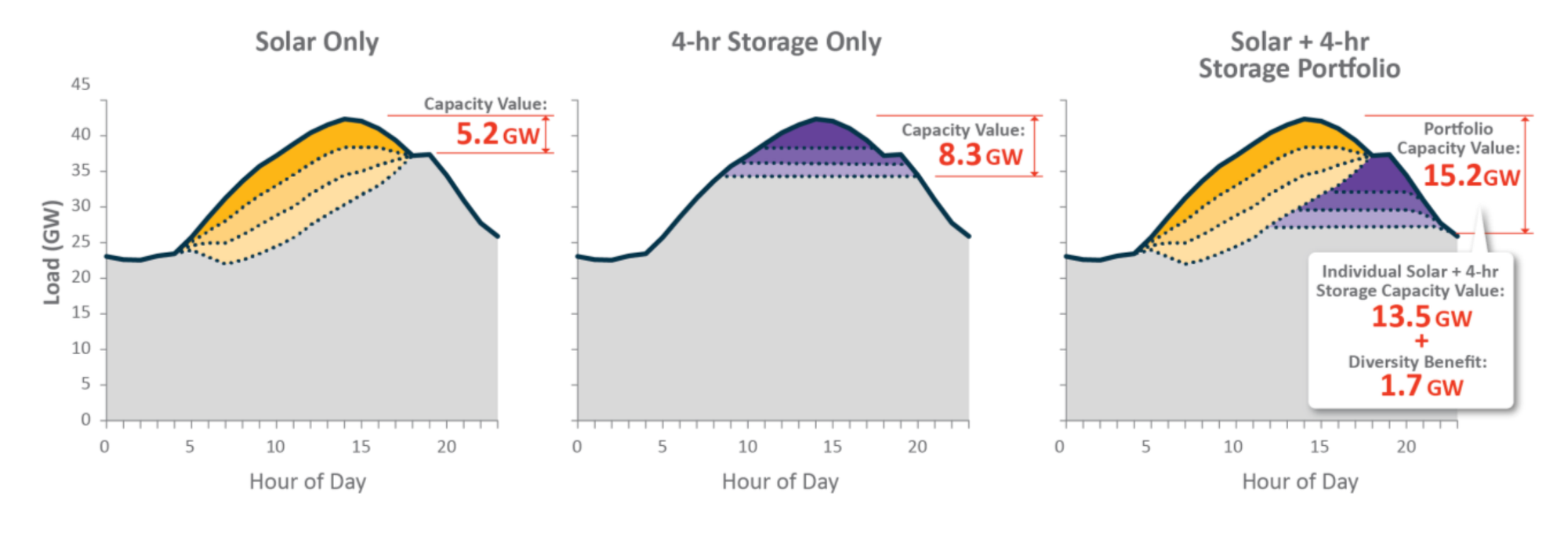

ELCC is a dynamic measurement affected by technology, the weather, grid infrastructure, and the existing resource mix. In other words, it changes as the grid and load change. Four-hour batteries might meet load on a full charge for a couple peaking hours. As more batteries are added, the ELCC of each marginal battery will drop because it will be used to meet increasingly non-peak portions of load–which likely last longer than the battery’s charge.

PJM’s gas turbines don’t have this problem because, unlike batteries, they don’t need to charge. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build batteries and renewables. In fact, if we add them alongside additional wind and solar, battery ELCCs will increase because we’ll have added charging capacity; emissions will fall. Resource diversity is good for ELCCs!

This is not to say PJM’s ELCC estimates adequately reflect storage’s capabilities or changes in its grid over the past year. What it could mean is that their managers are increasingly spooked by reliability tail risks absent additional clean firm resources like longer-duration batteries. Or they feel renewables aren’t increasing fast enough to both charge batteries and meet load. Both are solvable industrial policy problems!

A version of the diminishing ELCC effect is shown below for solar. Marginal solar additions shift peak events into nighttime hours, where solar is increasingly unable to meet load.

But if you add both solar and 4-hour batteries together, they cover more peak load than they could alone.

Paul Williams — Permits Approved, but No Construction?

A few months ago, The Boston Globe ran a feature story on residential construction in the city. One figure in particular stuck out: there are 23,000 apartments that have been approved—meaning they've cleared all zoning and permitting hurdles—but haven't moved a piece of dirt on the land. Why? Because they can't close on financing.

So even though they might have permits, no one will finance them. Tye has a project like that, the old Midtown Hotel on Huntington Avenue, where the city approved 325 units in 2021. But until financial markets improve, he said, those 325 apartments are on the shelf, along with almost 23,000 others around the city that have been approved but not yet built.

There are a few things going on here so let's do a basic review of multifamily finance. First you're going to need a mortgage—a senior loan. You might be able to get a loan at anywhere from 50% to 65% of total project cost. But the interest rate on those loans is closely tied to the 10-year Treasury yield, so when the Fed hikes rates, the mortgage gets more expensive. That's problem number one for these would-be builders.

Second, you need to fill the remaining capital gap. If you have good connections and a track record you might be able to fill some of it—but not all of it—with a subordinate debt product like a mezzanine loan. For the rest you need an equity investor. Private equity is where you get unyielding hurdle rates: investors know they are the last piece of the financing puzzle, and they aren't getting into the bed unless it's going to pay a 15% internal rate of return. So if your margins aren't that big, you leave your land sitting vacant, permits in hand, and the private equity investor goes off and invests in a semiconductor facility, or maybe a nice portfolio of senior living facilities instead.

So the question for policymakers, in the face of a 2 to 3 million unit housing gap, is how do we get these units built? Obviously making permitting and zoning approvals easier is a crucial first step, as many jurisdictions are waking up to, but in this case we're talking about tens of thousands of units that already cleared that hurdle and are still stuck. Now we need a financing tool.

A few weeks ago, Rachel Cohen at Vox published an article reviewing the deepening interest in the Montgomery County Housing Production Fund (disclaimer: CPE was also quoted in the story for our work with housing agencies across the country supporting this model)—including in Massachusetts. The CEO of the Boston Housing Authority, Kenzie Bok,

[...] was also intrigued by the potential of the revolving fund to spur more market-rate construction in Boston, which has slowed not only because of rising interest rates but also because institutional investors typically demand such high rates of return.

There is language to support these sorts of financing solutions for multifamily construction in the state's 5 year housing bill this session. We'll be watching closely to see if it moves forward and these public financing tools start to bring these 23,000 units online.

Advait Arun — Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Necessary but Insufficient Investment

Under what conditions does investment happen? Listen closely to financiers; you’re bound to get some answers. Project finance law firm Norton Rose Fulbright dropped a transcript of their “Cost of Capital: 2024 Outlook” webinar and, wow, it’s chock-full of insights worth sharing. My key takeaway is that the complex process for structuring energy transactions remains one of the biggest headwinds facing private-sector project development.

The speakers argued that the lack of deal standardization makes energy investment more complex: “We are hoping that the hybrid structure will settle into a less bespoke and more standardized product. We are now negotiating each such transaction uniquely. We believe it would be better for the market to have a standard approach.” This observation corroborates the arguments I made in our underwriting posts this past week.

Less surprisingly, broader macroeconomic trends tamped down deal volume last year, and the subsequent “loss of liquidity created upward pressure on rates,” pushing developers’ cost of capital up to around 7 percent, to say nothing of all the other tax equity-related loan products that developers also require to tide them over in advance of receiving their tax credit payments—loan products the speakers made clear lenders are charging steep discounts on due to their unfamiliarity and risk aversion.

Still, despite these constraints, the market has had its two best years ever. It’s booming so much, in fact, that there’s not enough underwriting capacity to go around, shutting newer developers out of quick access to financing: “There is a finite number of banks willing to process new deals because everyone is busy. People will work with their core relationships first.” If that isn’t an endorsement of our argument for building public underwriting capacity, I don’t know what else is!

(To get the best possible context into how lenders are deciding what to finance, I recommend reading this transcript yourself. And this, which just came out. There’s so much more about the different financing products that developers require; their costs of capital; debt service coverage ratios; and the relationships between solar, storage, the PTC, and the ITC.)

Yakov Feygin — ERCOT Grid Reliability

Texas’s ERCOT is a unique power system. Unattached to the rest of North America’s major grids, it has deep challenges with ensuring reliability. However, it also has seen some of the fastest deployment of renewable energy. To improve reliability after two years of seasonal crises, Texas has deployed a new program, the ERCOT Contingency Reserve Service (ECRS), which pays generators a fee to hold capacity that can ramp up to supply the grid in ten minutes.

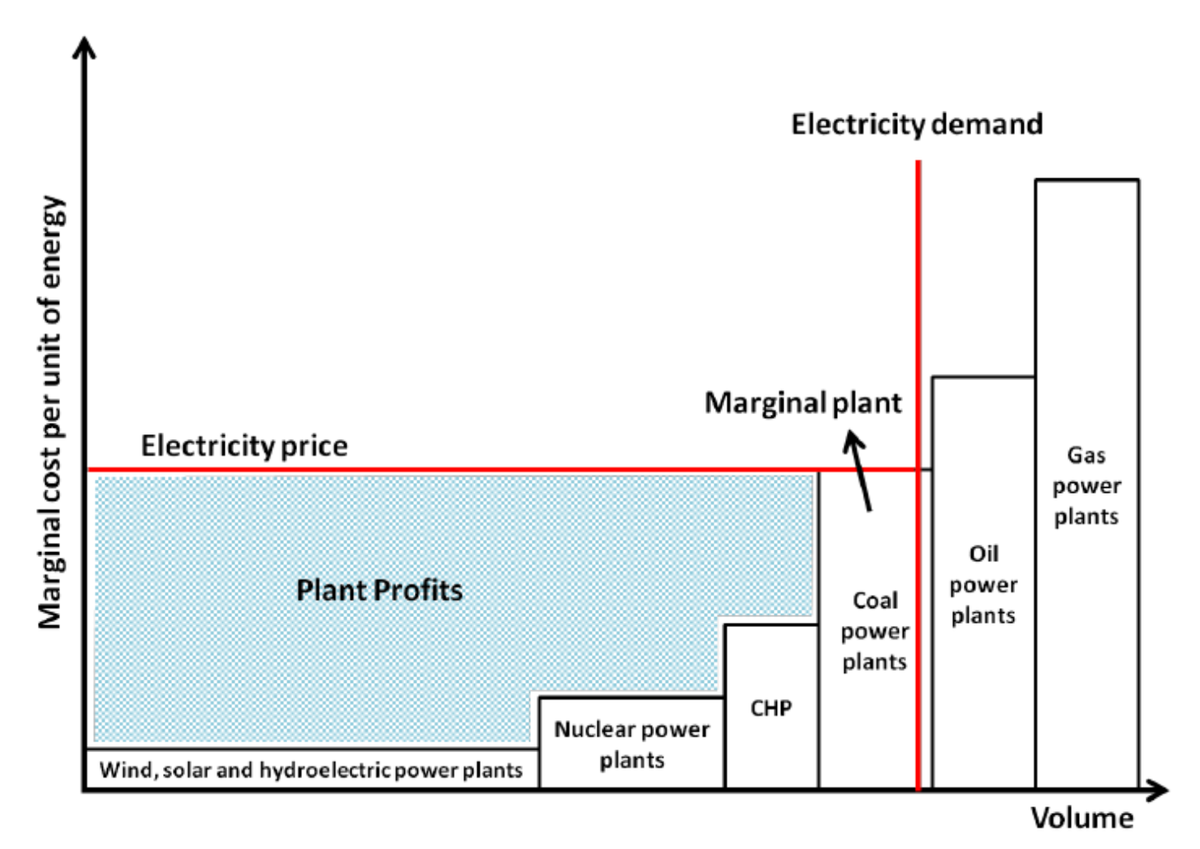

However, some critics of the program say it’s increasing consumer costs because it is preventing the most efficient gas plants—those that can spin up in ten minutes—from generating electricity during high-demand periods. Instead they are sitting on the sidelines and making money for holding their capacity in reserve. To make matters worse, it seems that these “reserve” plants then enter the market when prices are at their highest and make even more money selling the energy they were just paid to withhold. This happens because energy markets are structured around the “merit order.” Merit order is how prices are set in energy markets: potential generators place their bids into the market and utilities will pay the highest quoted bid that meets the marginal unit of demand—to all energy providers. In other words, to meet all of the given demand, utilities pay the price of the highest-cost resource required. More efficient sources line up behind this highest-marginal-cost bidder in the merit order and make more of a spread as a reward for their low-cost energy provision. When low supply and/or high demand for energy calls on high-marginal-cost resources–often older and less efficient coal and gas plants, to generate electricity–the “reserve” gas plants can essentially sneak into the middle of the merit order to capture that spread.

How did this happen? It seems this program was designed to promote battery storage. Storage is tricky. Batteries can incur costs when they are not discharging while only making money in the few hours they are feeding into the grid. That means they need a subsidy to provide capacity in high-demand hours. But Texas’s new subsidy is open to both batteries and gas plants. However, opening the ECRS program to gas plants, which have a completely different economics—they don’t lose money when they aren’t discharging into the grid—has had the unintended consequence of letting them game the system. As my colleague Chirag pointed out above, capacity, storage, and demand all move together in complicated ways. This requires direct planning of investment. Texas’s highly deregulated grid has, ironically, made it very difficult for private investors to play this role and has promoted the state government to direct public funds to incentivize the construction of gas peaking plants. However, even with these incentives, builders are not coming, prompting even some Texas politicians to consider publicly developing and owning gas plants.

Okay, thanks for reading Capacity Factor. As always, feel free to reach out if you have questions or comments. See you next month!