Capacity Factor, February 2024

Good morning. We're trying something new at Center for Public Enterprise this year, a monthly newsletter. The Capacity Factor is a monthly roundup of all things capacity: state capacity, infrastructure capacity, energy, housing, and so on and so forth...you get the idea.

Housing (Paul Williams)

Atlanta's new Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (AUDC) issued its first proposal for a 30-40 story mixed-income residential building. The public agency would maintain a controlling ownership stake in the property. As Axios put it last week:

The Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (AUDC), an Atlanta Housing subsidiary, announced a search for a developer to turn Fire Station 15 on 10th Street into mixed-income housing.

Intrigue: AUDC's goal is to build and maintain majority ownership on mixed-income housing on publicly-owned land without using Georgia's "scarce, over-tapped" tax credits.

We're not sure what the "intrigue" is, this is standard fare public enterprise.

Up in Rhode Island, the state Secretary of Housing, Stefan Pryor, selected the Furman Center at NYU to lead an implementation study for creating a "state housing developer" at the agency. Furman Center will do a good job with this, and will likely have some results for the state to make budget decisions by next quarter.

Pryor visited Montgomery County, Maryland, which is just north of Washington, D.C., in November [n.b. this was a Center for Public Enterprise hosted event] to see what's been built there and found one the developments there "impressive."

The "Montgomery County model," which has drawn attention in the national media, features buildings with a mix of apartments rented at market rates and below-market rates so tenants paying higher rents subsidize those paying less.

We're looking forward to following these developments closely and are anticipating several more such state and local public development programs to be announced in the coming quarter.

Interconnection (Chirag Lala)

Interconnection is increasingly understood as the major barrier to additional renewable and storage projects. The U.S. grid was largely set up to handle one-way power flows. But in a world of increasingly two-way flows, upgrades are needed: specialized inverters and additional transmission capacity especially. The planning and buildout for that capacity simply do not match the appetite for new generation and storage resources, resulting in queues with planned capacity that are now significant percentages of the already-installed capacity of their respective grid regions (and sometimes larger than total capacity itself)!

Not all of that capacity will ever interconnect: this is what a true bottleneck looks like. And it’s already affecting rate cases, as reluctant utilities cite interconnection costs to push back against renewable alternatives to continued gas investment. Reforms are needed—urgently.

A couple comments on this very good thread. First, note what is waiting to be built - it’s all clean. Markets aren’t trying to build dirty power because the economics don’t pencil. Our generation mix is getting a lot cleaner - not fast enough, but the forward build is clean. https://t.co/9Vb9cUvpUX

— Sean Casten (@SeanCasten) January 19, 2024

Note Sean’s point above that interconnection problems are because of the competitive structure under which the process makes determinations. Vertically integrated utilities simply build the interconnection capacity they need. That is, they have the legal authority to plan and execute interconnection upgrades without complex negotiations over the cost responsibility. Their grid upgrade determinations also reflect the risks they are willing to take on as grid managers. Reforms to interconnection for state distribution systems and the ISO/RTO systems would need to take lessons from the functions vertically integrated systems are able to carry out.

Energy Finance (Advait Arun)

I was tagged in this very interesting tweet (above) mentioning that CEOs seemed willing to accept lower rates of return for climate-friendly investments. I have previously written about private investors’ hurdle rates, their minimum acceptable rates of return, and judge that these CEOs’ answers might reflect greater competitiveness and/or higher demand across a range of clean investments—if they’re not giving overzealous answers, that is. I will be skeptical that private-sector hurdle rates have fallen until I see it in the data. The public sector, on the other hand…

Surveys from PwC showing ~40% CEOs are willing to accept lower hurdle rates for climate-friendly investments (vs ~25% 5yrs ago)

— Anderson Lee (@andersonleenyc) January 18, 2024

Most investors support firms making ESG capex even with lower ST profitability

ht @hscotthiggins cc @advaitarun_ @IrvingSwisher @theilmatic @deangranoff pic.twitter.com/V3QXu09rSL

I also read this Bloomberg piece, a short feature of an investment manager complaining that the IRS’s tax credit rulemaking has been too slow, that tax equity financing for clean energy investments remains too complicated: “Renewable energy infrastructure in the US is highly dependent on an overly complex and ultimately fragile system for placing an important part of the capital stack for these projects.” I can’t say I disagree—throw in interest rate volatility and supply chain snarls and the fact that potential changes to banking regulations could seriously kneecap the tax equity market and, yeah, this is all pretty fragile. Public developers that can access elective pay rather than relying on tax equity might actually be better positioned than their private counterparts.

Renewables (Yakov Feygin)

Another Bloomberg story that caught our attention covers the financing problems of the rooftop solar sector in California. California was the nation’s leader in rooftop solar, creating a boom in installations. But today, 63% of 400 surveyed installers report having a cash flow problem. Some of the trouble comes from a well-known problem in the renewable energy space: higher than expected interest rates. We’ve also seen this contribute to the difficulties of larger scale projects like offshore wind. What Bloomberg’s new coverage points out that the same problems are starting to be felt in the distributed energy sector.

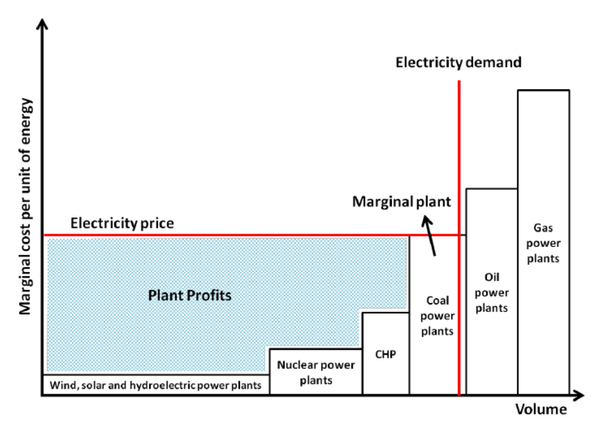

When we dig a bit deeper into the story, we find another interesting pressure on the finances on rooftop developers. In 2022, California changed how it reimburses owners of rooftop solar. Instead of paying a fixed rate for rooftop solar sold into the grid, California’s Public Utility Commission has adopted an “avoided cost calculation” (ACC) to set rates. The ACC means that instead of being paid for energy generated at peak hours at a fixed rate, new rooftop units will get paid less when demand for electricity is low and more when it is high. This is good for balancing the grid but bad for homeowners who used to make a killing on the arbitrage the old rules provided, with wealthy households benefiting most.

Without this piggy bank, rooftop solar isn’t as easy to finance. All this gets us to a broader question: How distributed is the future of distributed energy? As distributed energy scales, it starts to look a lot more like balancing grid-level supply and demand will mean every distributed owner will have to be a bit like their own power plant, using batteries to capture excess energy to sell into the grid when generation is low and prices are high. Distributed solar starts looking a lot like it needs a bit more public sector coordination, of the sort that is helping utility scale projects hold on in challenging financial times

The Grid (Advait Arun)

Bloomberg ran a noteworthy piece about investment strategies in the energy sector: “While investments in wind and solar mostly resulted in losses in 2023, fund managers who piled into companies tied to the electrical grids that distribute clean energy enjoyed double-digit returns.” The piece argues that investors can capture substantial returns from investments in electricity transmission and distribution, particularly due to slow grid expansion and supply chain bottlenecks in sold-out critical transmission components like transformers.

What this article really suggests to me is that the lack of capacity expansion in this sector—many renewables generation projects remain stuck in interconnection queue limbo across the country—makes it extremely prone to rent-seeking behavior from investors. There’s money to be made in betting on rising electricity demand and rising ratepayer cashflows across the country, but, as revealed by the lack of adequate capacity expansion to match, good cashflows for investors do not necessarily imply that their investments are socially useful. It’s not clear that private investors will rechannel their rents into facilitating greater grid capacity expansion. Public sector firms charged with meeting grid expansion goals, on the other hand, could be directed to do so—rechanneling rents from people’s electricity bills back to people in the form of cleaner and more efficient energy grids.

State Capacity (Paul Williams)

The IRS launched two exciting portals on its website this month: one for tax-exempt energy developers (e.g. public utilities), and one for average taxpayers: the Elective Pay and the Direct File tools.

Elective Pay, which we've written about extensively, received a new registration portal called Energy Credits Online. The tool allows elective pay eligible entities to pre-register their projects, helping ensure eligibility and reduce risk.

Direct File, on the other hand, is a brand new IRS website that allows normal taxpayers to file their annual income taxes directly with the IRS, on IRS.gov.

This tool has been a long time coming—ever since the advent of the World Wide Web, the IRS has had agreements with third party tax prep firms like Intuit (TurboTax), giving them a near-monopoly on tax filing activities.

We're excited to see this program expanded to more and more taxpayers in the years to come.

That's the big news for this month. We hope you enjoyed our first monthly roundup—please feel free to offer us your feedback at info@publicenterprise.org.